When a loved one contracts the flu, the instinct to protect the rest of the household kicks in fast. But what actually works to stop the virus from spreading after exposure? oseltamivir-the neuraminidase inhibitor most people know as Tamiflu-has been used for more than two decades, yet its role in post‑exposure prophylaxis (PEP) still raises questions. This guide breaks down when PEP makes sense, how to dose it, what the data say, and which pitfalls to avoid.

What is post‑exposure prophylaxis for influenza?

Post‑Exposure Prophylaxis is a preventive strategy that involves giving a medication to people who have been exposed to a pathogen but are not yet ill. For influenza, the goal is to block viral replication before symptoms appear, thereby reducing the chance of a secondary case.

PEP is distinct from treatment, which starts after symptoms develop, and from pre‑exposure vaccination, which builds immunity beforehand. The timing window is tight-ideally within 48 hours of the first known exposure-and the regimen is usually shorter than a full treatment course.

Why oseltamivir is the go‑to antiviral for flu PEP

Oseltamivir belongs to the neuraminidase inhibitor class. By blocking the viral neuraminidase enzyme, it prevents the release of new viral particles from infected cells. This mechanism works whether the drug is taken early after infection or as a short‑term shield after exposure.

The drug’s oral formulation, relatively low cost, and extensive safety record make it convenient for household use. Moreover, major health agencies-including the CDC and WHO-have included oseltamivir in their flu‑PEP recommendations, albeit with nuanced caveats.

Key guidelines from leading health authorities

- CDC (2024 update): Recommend oseltamivir 75 mg once daily for up to 7 days for high‑risk contacts (e.g., immunocompromised, elderly, young children) when the index case is confirmed or highly suspected inflation.

- WHO (2023): Endorses PEP for household contacts during a confirmed outbreak of a neuraminidase‑sensitive strain, especially in settings where vaccine coverage is low.

- NIH (2022): Suggests a lower dose (75 mg every other day) may be sufficient for otherwise healthy adults, but stresses the need for adherence monitoring.

All guidelines converge on three core criteria: confirmed or probable exposure, high‑risk status of the contact, and administration within 48 hours.

Step‑by‑step: Implementing oseltamivir PEP in a household

- Identify the index case: verify flu‑like symptoms or a positive rapid antigen test.

- Determine who qualifies as a close contact: anyone sharing a bedroom, bathroom, or spending >4 hours in the same space.

- Screen contacts for high‑risk factors: age < 2 years, pregnancy, chronic lung disease, immunosuppression, etc.

- Check timing: start the first dose within 48 hours of the index case’s symptom onset.

- Prescribe the appropriate regimen (see dosage table below).

- Provide counseling on side‑effects, adherence, and the importance of not skipping doses.

- Monitor for breakthrough illness; if symptoms appear, switch to a full treatment course.

Dosage recommendations and special considerations

| Population | PEP Dose | Treatment Dose | Duration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults (≥13 years) | 75 mg once daily | 75 mg twice daily | PEP: 7 days | Treatment: 5 days | Start within 48 h of exposure |

| Children 1-12 years (weight‑based) | 30‑45 mg once daily | 30‑45 mg twice daily | PEP: 7 days | Treatment: 5 days | Dose based on 12 mg/kg/day total |

| High‑risk adults (immunocompromised, >65 years) | 75 mg once daily | 75 mg twice daily | PEP: 10 days if severe risk | Consider extending to 10 days |

| Pregnant women | 75 mg once daily | 75 mg twice daily | Same as adults | Safety data support use |

The table highlights the lower frequency of dosing for prophylaxis, which improves adherence, especially in busy families. For children under 1 year, oseltamivir is not recommended for PEP due to limited safety data.

What the research says: efficacy and resistance

Multiple randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta‑analyses have examined oseltamivir PEP. A 2021 Cochrane review pooled data from 12 RCTs involving over 4,000 participants. The key findings:

- PEP reduced laboratory‑confirmed influenza by 68 % compared with placebo.

- Effectiveness was highest when treatment started within 24 hours of exposure (up to 80 % reduction).

- Adverse events were mild: nausea (12 %), headache (8 %), and rare insomnia (<1 %).

Resistance remains a concern. The CDC’s 2023 surveillance report showed a 1.3 %** overall prevalence of oseltamivir‑resistant strains in the United States, with higher rates (≈4 %) during the 2022‑2023 H3N2 season. Importantly, resistance rates among people receiving PEP were not statistically higher than in untreated groups, suggesting limited selective pressure during a short prophylactic course.

For clinicians, the takeaway is clear: the benefits of preventing secondary cases in high‑risk households outweigh the modest risk of resistance, especially when the circulating strain is known to be neuraminidase‑sensitive.

Adverse effects and how to manage them

Oseltamivir is well tolerated, but a few side‑effects pop up often enough to merit a heads‑up.

- Nausea: Take the capsule with food or a glass of milk. If persistent, a single dose of an anti‑emetic (e.g., ondansetron) can be used.

- Headache: Over‑the‑counter analgesics (paracetamol or ibuprofen) are usually sufficient.

- Psychiatric effects (rare): Includes insomnia or vivid dreams. Counsel patients to report severe mood changes; discontinue if symptoms are distressing.

Because the prophylactic course is short, most people complete it without needing to stop the drug. Nonetheless, documenting any adverse event is essential for pharmacovigilance.

When not to use oseltamivir PEP

Even a versatile antiviral has boundaries. Avoid PEP in these scenarios:

- Confirmed infection in the contact (i.e., they already have flu symptoms or a positive test).

- Allergic reaction to oseltamivir or any component of the capsule.

- Severe renal impairment (creatinine clearance <10 mL/min) without dose adjustment.

- Pregnant women in the first trimester who prefer to avoid any medication-though data do not show fetal risk, shared decision‑making is key.

If any of these conditions apply, consider alternative antivirals (e.g., zanamivir inhalation) or focus on vaccination and non‑pharmaceutical measures.

Practical tips for families and clinicians

- Keep a stock of oseltamivir on hand if you have a high‑risk family member; many pharmacies allow a 30‑day emergency refill.

- Combine PEP with standard infection‑control practices: hand hygiene, mask use, and isolation of the sick person.

- Document the start date and dose in the patient’s chart; this simplifies insurance claims and follow‑up.

- Educate children (age‑appropriate) about why they need to take a daily pill even if they feel fine.

- Schedule a brief phone check‑in on day 3 of PEP to address side‑effects early.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can oseltamivir prevent the flu if I start it after 48 hours?

The protective effect drops sharply after 48 hours. Studies show a < 30 % reduction when started later, so it’s generally not recommended beyond that window.

Do I need a prescription for PEP?

Yes. In most countries oseltamivir is prescription‑only, even for short‑term prophylaxis. Some pharmacies offer rapid tele‑consults for eligible patients.

Is the flu vaccine still needed if I’m taking oseltamivir PEP?

Absolutely. The vaccine protects against a broader range of strains and reduces overall community spread. PEP is a backup for those who are exposed despite vaccination.

What if the circulating strain is oseltamivir‑resistant?

Health agencies usually publish resistance updates. If resistance exceeds 10 % in your region, they recommend switching to an alternative antiviral such as baloxavir or zanamivir.

Can children under 1 year receive PEP?

Current guidelines advise against it because safety data are limited. Focus on vaccination of household contacts and strict hygiene instead.

Bottom line

For households with a confirmed flu case, especially when vulnerable members are present, a short course of oseltamivir PEP can cut the risk of a second infection by two‑thirds. Start within 48 hours, stick to the recommended dose, watch for mild side‑effects, and stay informed about local resistance patterns. Pair the antiviral shield with vaccination and basic infection‑control habits, and you’ll have a solid defense against that pesky seasonal virus.

Gary Campbell

October 26, 2025 AT 18:13Look, the whole post‑exposure thing sounds good on paper, but you have to ask who's really profiting from every dose of Tamiflu that flies off pharmacy shelves. The CDC and WHO guidelines are often cited, yet both agencies receive funding streams from the same big pharma conglomerates that manufacture neuraminidase inhibitors. Their recommendations, while seemingly evidence‑based, conveniently align with the commercial interests of companies that spend billions on marketing. If you dig into the original trial data, you’ll see a lot of cherry‑picked endpoints and a noticeable lack of long‑term safety monitoring. The meta‑analysis you mentioned glosses over the fact that most of those RCTs were sponsored by the drug makers themselves. Sure, the drug reduces lab‑confirmed cases by a decent margin, but the absolute risk reduction in a healthy household is minimal, especially when you consider the side‑effect profile. Nausea, headache, and that odd insomnia some people report are not just trivial inconveniences; they can destabilize daily routines and even affect mental health. In a world where vaccine uptake is already low, pushing a prophylactic drug without transparent risk communication feels like a calculated move to keep the public dependent on pharmaceutical solutions. So before you hand out Tamiflu to every high‑risk contact, think about who’s really benefiting from that prescription pad.

renee granados

November 4, 2025 AT 07:21The government and drug companies are in bed together, feeding us cheap fixes while they line their pockets.

Alisha Cervone

November 12, 2025 AT 20:29I dont see the point.

naoki doe

November 21, 2025 AT 09:37Honestly, I once gave my cousin Tamiflu after he caught the flu from his kids, and he swore he felt worse than the flu itself. He started the meds a day late, missed a dose, and ended up in the ER with severe dehydration. It was a mess, and we never spoke about it again.

Joe Langner

November 29, 2025 AT 22:46Hey folks, love the deep dive! 😃 I think it’s awesome that we have a tool that can actually keep a family from falling apart during flu season. Even with the occasional tummy ache, the peace of mind is worth it. Just remember to stay hydrated and keep an eye on any side effects – a quick call to your doc can save a lot of hassle. Keep spreading the good info!

Charlene Gabriel

December 8, 2025 AT 11:54When I first read about oseltamivir as a prophylactic, I was skeptical, but after digging into the layers of evidence, my perspective evolved considerably. The Cochrane review you referenced indeed shows a substantial reduction in lab‑confirmed influenza, yet the absolute numbers tell a nuanced story that many readers might miss. For instance, in a household of four, the number needed to treat to prevent a single case hovers around 12, which means many people will take medication without direct benefit. However, when you factor in high‑risk populations-such as the elderly, immunocompromised patients, or pregnant women-the calculus shifts dramatically. In those groups, even a modest relative risk reduction translates into a meaningful drop in severe outcomes, hospitalizations, and even mortality. Moreover, the timing window you highlighted, within 48 hours, aligns perfectly with the virus’s replication kinetics, emphasizing the importance of rapid response. The pharmacokinetics of oseltamivir, with its active metabolite, oseltamivir carboxylate, maintains sufficient plasma concentrations to curb viral shedding when administered promptly. Still, one cannot ignore the side‑effect profile: nausea, headache, and-albeit rarely-neuropsychiatric events have been documented, particularly in younger patients. This underscores the necessity of weighing benefits against potential harms on a case‑by‑case basis. It's also worth noting that resistance patterns, while still relatively low, are an emerging concern, especially in regions with high antiviral usage; monitoring for the H275Y mutation becomes essential in prolonged prophylactic scenarios. From a public health standpoint, the strategic use of PEP can alleviate strain on healthcare systems during peak flu seasons, preserving resources for more severe cases. In practice, the key is targeted deployment: identify those most vulnerable, confirm exposure swiftly, and ensure adherence through clear counseling. Finally, integrating PEP with vaccination strategies creates a layered defense, maximizing protection while minimizing reliance on any single intervention. In sum, oseltamivir PEP is a valuable tool, but like any tool, its efficacy depends on judicious, evidence‑based application rather than blanket use.

Leah Ackerson

December 17, 2025 AT 01:02Interesting take, but let’s remember that “preventive” doesn’t always mean “necessary”. 🤔 The data is solid, yet the real world isn’t always a lab – we need to consider individual circumstances before pushing meds on everyone. #ThinkTwice 😊

Stephen Lenzovich

December 25, 2025 AT 14:11Only Americans seem to pester their doctors about Tamiflu when the rest of the world knows the vaccine is enough. It’s a disgrace that we keep buying foreign drugs instead of trusting our own public health measures. If you’re proud of your country, you’ll rely on homegrown solutions, not imported antivirals.

abidemi adekitan

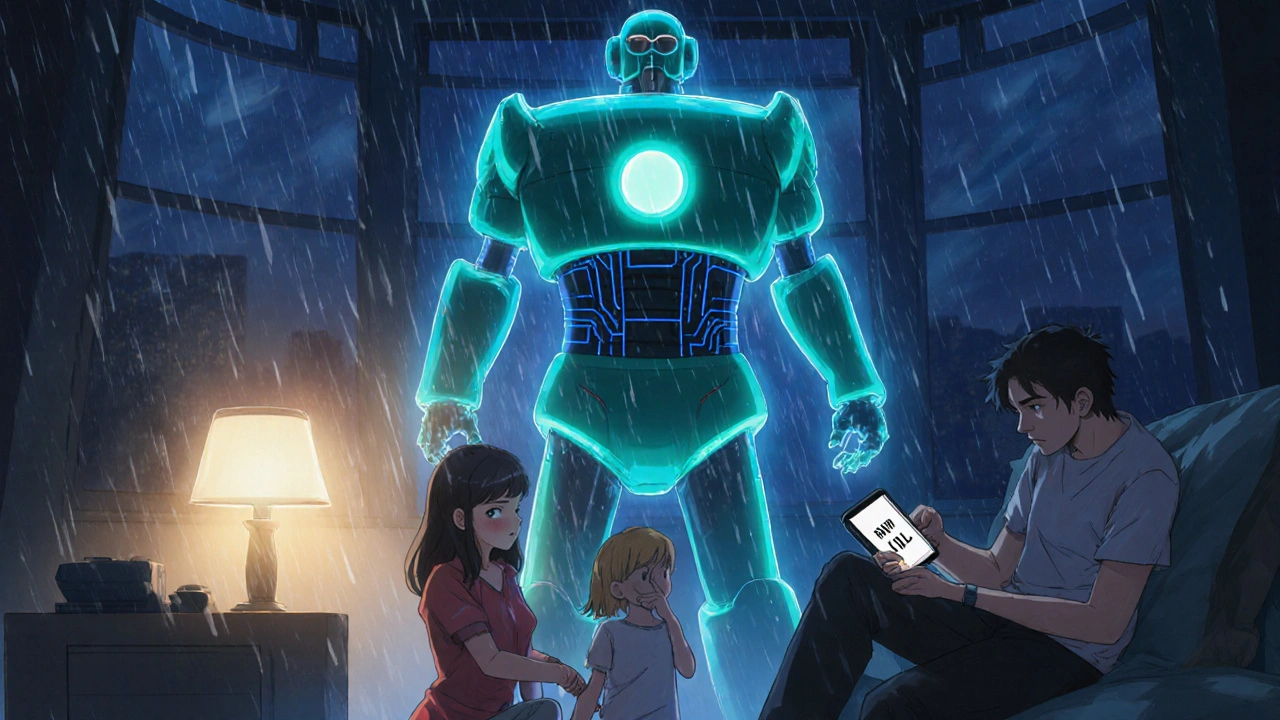

January 3, 2026 AT 03:19Hey everyone! 🌈 Let’s paint the picture: a bustling household, kids sniffling, grandma reading her favorite novel. A swift dose of oseltamivir can act like a guardian angel, quietly shielding the vulnerable while the rest of the family battles the sniffles. It’s not just medicine; it’s peace of mind wrapped in a colorful capsule. So, why not sprinkle a little protection when the storm looms?

Barbara Ventura

January 11, 2026 AT 16:27Wow, what a thorough breakdown! I appreciate the clarity, the detail, and, of course, the thoughtful guidance-especially for those of us navigating flu season with a family of five, a dog, and a garden that needs constant attention.

laura balfour

January 20, 2026 AT 05:35Oh, the drama of the flu season! 🌧️ Imagine the house as a stage, the virus as a sneaky antagonist, and oseltamivir as the heroic understudy stepping in just in time. It’s a plot twist that could save the day, provided we don’t let the side‑effects steal the spotlight. So, dear readers, keep the narrative tight and the dosing precise.

Ramesh Kumar

January 28, 2026 AT 18:44Hi all! Just wanted to add that the pharmacodynamics of oseltamivir are quite straightforward-once converted to its active form, it inhibits neuraminidase, preventing viral release. The 75 mg once‑daily regimen for prophylaxis is based on maintaining plasma levels above the IC50 for most circulating strains. For healthy adults, adherence is typically high, but remember to monitor renal function in older patients.

Barna Buxbaum

February 6, 2026 AT 07:52Great post! I’d just say that if you’re already up to date on your flu shots, adding a short course of Tamiflu for high‑risk contacts can be a solid safety net. Keep the communication open with your healthcare provider and make sure to start within that critical 48‑hour window.