It’s 2026. You walk into your pharmacy looking for a cheaper version of your monthly prescription. The pharmacist says, "It’s FDA-approved. We just can’t get it." This isn’t a glitch. It’s the new normal.

Between 2023 and 2025, hundreds of generic drugs received final approval from the FDA - only to sit on shelves, unavailable to patients. The reason? Not quality issues. Not supply chain breakdowns. Not manufacturing delays. It’s patent litigation. Brand-name drug companies are using the legal system to stretch monopolies far beyond what Congress intended.

How the System Was Supposed to Work

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 was designed to balance innovation and access. It gave brand-name companies 20 years of patent protection. In return, it let generic makers file applications years before those patents expired - as long as they promised to challenge any invalid patents. That’s called a Paragraph IV certification. It’s supposed to be a shortcut to lower prices.

But here’s what happened: instead of one patent to fight, generic companies now face 14 or 15 patents per drug. The average New Drug Application listed 12.3 patents in 2020. By 2025, that number jumped to 14.7. These aren’t all groundbreaking inventions. Many are minor tweaks - new dosages, packaging, or delivery methods. But under current rules, each one triggers a 30-month legal stay. That’s a federal pause on the FDA’s ability to give final approval, no matter how strong the generic maker’s case is.

The Real Bottleneck: Patent Thicketing

Drug Patent Watch found that 68% of all generic applications filed in 2024 included Paragraph IV certifications. That’s up from 54% in 2020. But here’s the twist: the brand companies aren’t just defending one patent. They’re filing dozens, sometimes hundreds, to create what experts call a “patent thicket.”

Take Humira. Its core patent expired in 2016. But AbbVie filed over 240 patents related to it. Each one triggered a new 30-month clock. The result? Generic versions didn’t launch until 2023 - seven years after the original patent ran out. That’s not innovation. That’s legal engineering.

Dr. Aaron Kesselheim from Harvard Medical School put it bluntly: “The current patent thicketing strategies have extended monopolies beyond the intended 20-year term by an average of 3.7 years per drug.”

Why Approval Doesn’t Mean Availability

The FDA approved 63 first generics in 2025. Sounds good, right? But according to a 2024 study in the Journal of Generic Medicines, the average time between FDA approval and actual market launch is now 3.2 years. For complex drugs like injectables and inhalers, it’s even longer - up to 4.1 years in oncology.

Why? Because even after the FDA says a generic is safe and effective, the brand company can still sue. And the law forces the FDA to wait. No matter how clear the generic maker’s legal position is. No matter how many patients are struggling to pay $500 a month for a brand drug that should cost $85.

Pharmacists are seeing this firsthand. A September 2025 survey by the Association for Accessible Medicines found 82% of them get daily calls from patients asking why their approved generic isn’t in stock. The top drugs? Eliquis, Trulicity, Steglatro - all with FDA approval but blocked by lawsuits.

Who Gets Hurt the Most

Patients pay the highest price - literally. Patients For Affordable Drugs Now documented 412 cases between 2023 and 2025 where people skipped doses or went without medication because generics weren’t available. The average monthly cost for the brand-name version? $487. The projected cost for the generic? $85.

Medicare Part D spent $3.2 billion more in 2025 because of these delays, according to the Congressional Budget Office. That’s taxpayer money going straight into the pockets of brand-name companies.

Small generic manufacturers are getting crushed, too. RBC Capital Markets found that 63% of delayed generics involved companies with annual revenue under $500 million. Legal costs? $12.7 million per case in 2025 - up from $9.3 million in 2023. Most can’t afford to fight. Big companies like Teva and Sandoz can. But they’re the exception.

Supply Chains and Other Delays

Patent fights aren’t the only problem - but they’re the biggest. Supply chain issues contributed to 37% of delays between 2023 and 2025, especially for injectables. The same PMC study found 14 out of 15 oncology drug shortages involved complex generics. But even here, patent litigation is often the root cause. Why? Because brand companies control the reference samples needed for testing. If they refuse to sell them - which they’ve done in dozens of cases - the generic maker can’t even begin the approval process.

The CREATES Act was written to fix this. It would force brand companies to provide samples. But as of September 2025, it was still stuck in committee.

What’s Changing - and What’s Not

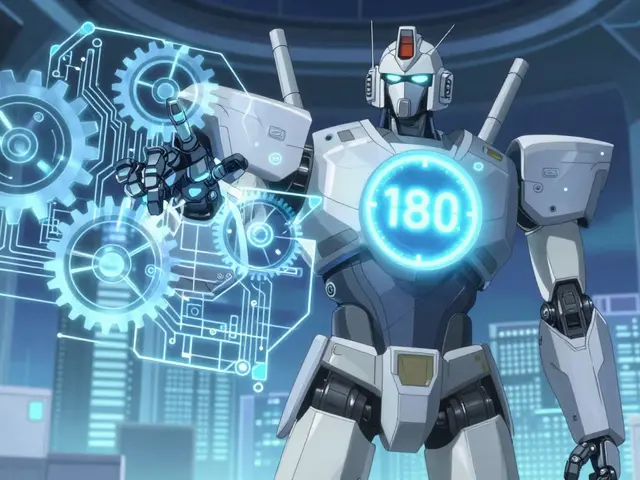

The FDA has tried to speed things up. Its new AI-assisted review system cut review times by 22% for non-litigated applications. The National Priority Voucher program promises 1-2 month reviews for certain drugs. But none of this touches the 30-month stay. That’s controlled by courts - not the FDA.

Even the Orange Book, the official list of patents linked to drugs, is a mess. Dr. Patrizia Cavazzoni, director of the FDA’s drug center, admitted in May 2025 that the agency is working to clean it up. “We’re trying to prevent evergreening,” she said. But without Congress changing the rules, it’s like mopping the floor while the faucet is still running.

Meanwhile, the European Union moves faster. Their average time from approval to launch? 1.7 years. The U.S.? 3.2. Why? Because Europe doesn’t have the same 30-month legal pause. If a patent is weak, generics can launch immediately. In the U.S., they have to wait - even if the court rules the patent is invalid.

The Future: Will Anything Change?

There’s momentum. The FTC filed seven enforcement actions between 2024 and 2025 against companies using patent tactics to block competition. One case against Jazz Pharmaceuticals over Xyrem led to an agreement forcing earlier generic entry.

McKinsey & Company found 67% of industry stakeholders support limiting how many patents can be listed per drug. But PhRMA, the drug industry lobby, is fighting back hard. They argue any change would hurt innovation. But innovation isn’t about filing 240 patents on one drug. It’s about creating new treatments - not extending old ones.

And then there’s the political will. The 118th Congress didn’t pass the CREATES Act. The FDA’s new commissioner, Dr. Peter Bach, is pushing for more transparency in patent listings. If he succeeds, generic entry could speed up by 8-12 months by 2027.

But right now, the system is broken. Patients are paying more. Pharmacists are powerless. Generics are approved - but locked out.

The question isn’t whether generics can be made. They can. The question is whether the law will let them reach the people who need them.

Why are generic drugs approved by the FDA but still not available?

Even after the FDA approves a generic drug, its launch can be blocked by patent lawsuits from the brand-name manufacturer. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act, when a generic company files a Paragraph IV certification challenging a patent, the brand company can sue - triggering a mandatory 30-month legal stay. During this time, the FDA cannot give final approval, no matter how strong the generic’s legal position. This delay is not about safety or quality - it’s a legal tactic to extend market exclusivity.

What is a Paragraph IV certification?

A Paragraph IV certification is a legal statement filed by a generic drug maker with the FDA, claiming that a brand-name drug’s patent is either invalid or won’t be infringed by the generic version. This triggers a 30-month stay if the brand company sues. It’s the main tool generics use to challenge patents and enter the market early - but it’s also the trigger for most delays.

How many patents are typically listed for one drug?

In 2020, the average New Drug Application listed 12.3 patents. By 2025, that number rose to 14.7. Some drugs, like Humira, have over 240 patents listed. Many of these are minor variations - new formulations, delivery methods, or packaging - not true innovations. But each one can be used to trigger a new 30-month legal delay.

Why are complex generics like injectables delayed longer?

Complex generics - such as injectables, inhalers, and topical products - face longer delays because they’re harder to replicate and require more testing. But the biggest reason is patent litigation: 89% of delayed complex generics face patent-related blocks, compared to 63% of simple oral pills. Brand companies often use patent thickets to protect these high-margin products, knowing generic makers lack the resources to fight multiple lawsuits.

What’s the difference between the U.S. and Europe on generic delays?

In the U.S., the 30-month legal stay forces generics to wait even if a patent is weak. In Europe, there’s no automatic stay. If a generic challenges a patent and the court doesn’t rule in the brand’s favor quickly, the generic can launch. As a result, the average time from approval to launch is 1.7 years in Europe versus 3.2 years in the U.S. The U.S. system prioritizes legal process over patient access.

Are biosimilars facing the same delays?

Yes - and even more so. Biosimilars, which are complex versions of biologic drugs, face an even more tangled patent landscape. The average number of patents challenged per biosimilar application jumped from 5.2 in 2020 to 9.7 in 2025. Humira’s biosimilars faced over 240 patents before launch. But approvals are increasing: 17 biosimilars were approved by Q3 2025, up from just a handful in 2020. Still, litigation delays remain a major barrier.

What can be done to fix this?

Three key fixes are needed: First, cap the number of patents that can be listed per drug - right now, there’s no limit. Second, eliminate or shorten the 30-month stay so it doesn’t automatically block access. Third, enforce the CREATES Act to require brand companies to provide samples for testing. The FTC has started taking action, and public pressure is growing. But without congressional reform, these delays will continue.

Edith Brederode

January 20, 2026 AT 09:47This is heartbreaking 😔 I had a friend who skipped her diabetes meds for 3 months because the generic was approved but locked up in litigation. She ended up in the ER. This isn’t just policy-it’s life or death. Why are we letting corporations profit off suffering?

Renee Stringer

January 22, 2026 AT 07:21The system is designed to fail patients. Every time a patent is filed for a new capsule color or dosing schedule, it’s a deliberate delay tactic. The FDA can approve all it wants-but if the law protects greed over access, nothing changes. This is institutionalized theft.

kumar kc

January 23, 2026 AT 06:12USA has the most expensive drugs in the world. This is why.

Jacob Cathro

January 24, 2026 AT 11:43so like… pharma companies are just… spamming patents? like, 240 for one drug?? bro that’s not innovation that’s a legal glitch exploit. also why is the fda just sitting there? they could at least blacklist companies that do this. #patentabuse

Thomas Varner

January 25, 2026 AT 02:00It’s wild how the system rewards legal maneuvering over actual medicine… I mean, we’ve got AI reviewing applications faster now, but the 30-month stay? Still standing. Like, we’re optimizing the wrong part of the pipeline. It’s like upgrading the engine while the brakes are welded down.

Emily Leigh

January 26, 2026 AT 10:24so… if the FDA says it’s safe, why are we letting lawyers decide who gets medicine?? this isn’t capitalism, this is feudalism with better lawyers… and also… who’s paying for all these lawsuits? taxpayer dollars?? of course they are. 🤡

Shane McGriff

January 26, 2026 AT 12:16Let’s be real: the 30-month stay isn’t a safeguard-it’s a weapon. And it’s being used on drugs that cost $500 a month when they should be $85. Patients are skipping doses, skipping meals, choosing between insulin and rent. Meanwhile, Big Pharma’s stock prices are up 18% last quarter. This isn’t a policy failure. It’s a moral failure. And the fact that the CREATES Act is still stuck in committee? That’s not incompetence. That’s corruption.

Europe doesn’t have this problem because they don’t let lawsuits override public health. We could fix this tomorrow if we wanted to. We just don’t want to. Because the people who benefit from this system? They write the laws.

And don’t get me started on reference samples. If a brand company refuses to sell you the drug so you can test a generic? That’s not competition. That’s sabotage. The CREATES Act isn’t radical-it’s basic. It’s like requiring a car maker to give you the engine specs before you can build a compatible part. Why is this even a debate?

Small generics? They’re getting crushed. $12.7 million per lawsuit? Most can’t even afford the filing fee. Teva and Sandoz can fight. But what about the smaller players? The ones who actually want to help? They’re being pushed out. And the worst part? The public doesn’t even know. We think the drug’s just ‘out of stock.’ We don’t realize it’s being held hostage.

And yes-biosimilars are worse. 9.7 patents per application? That’s not science. That’s a legal minefield. We’re talking about life-saving treatments for cancer, autoimmune diseases… and we’re letting patent trolls block them. This isn’t innovation. It’s extortion.

There’s momentum. The FTC is acting. The public is angry. But until Congress acts, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. And the patients? They’re still in the water.

Art Gar

January 26, 2026 AT 19:27While I appreciate the emotional appeal, the reality is that without robust patent protection, innovation would collapse. The R&D costs for these drugs are astronomical. If generics could flood the market immediately, no company would invest in new therapies. The 30-month stay is not a loophole-it’s a necessary incentive structure. The real issue is not patent thickets, but the failure of Congress to fund public research alternatives. We cannot have both cheap generics and groundbreaking science without public investment.

Carolyn Rose Meszaros

January 28, 2026 AT 13:21Thank you for posting this. I’m a pharmacist in Ohio and I see this every day. Patients cry because they can’t afford their meds. We have the generics. We have the approval. We just don’t have the access. 🙏 I’ve started printing out these stats and leaving them on the counter. Someone needs to see it.

Crystal August

January 30, 2026 AT 03:08So let me get this straight… the system is rigged so that the same companies that made the drug can block the cheaper version… by filing patents on the color of the pill?? This is not capitalism. This is a cartoon villain plot. And the FDA is just… watching? Like, what’s their job? To stamp ‘approved’ and then go home? This is why people hate institutions.